Welcome to the MWH Wine Definitive Guide to Port. In this guide we’ll answer the most frequently asked questions about this wonderful wine. We’ll tell you what is Port wine? What is vintage Port? How to decant port? What is a late bottled vintage Port, which is the best Port producer, and how long does vintage Port last once it’s been opened?

This guide has been put together by the MWH Wine team who are known as one of the UK’s leading Port wine merchants. MWH Wine has been described by Jancis Robinson MW as, ‘An exceptional source of mature Ports’. You can buy vintage Port from us that dates back to the 1940s, including the fabled 1945 vintage Port.

We hope you will enjoy reading this guide to Port wine. If you are looking for a specific vintage Port, then please do get in touch by calling Mike on 0118 984 4654 or by emailing MWH Wines here. A recognised authority on these wines, he’ll be happy to advise you on which Port is right for you.

A Brief History of Port Wine

Grapes have been grown and wine has been made in Portugal since around 2000 BCE. However, Port as we know it today came about in the 17th century, in part thanks to English merchants and English tastes. When trading rivalries between the French and English resulted in higher duties and then import bans on French wines, English merchants sought alternative supplies.

It was found that the robust and full-bodied wines produced in the Douro Valley were well-liked by the English. Due to the distance from the coast, where English merchants resided, and the mountainous terrain of the Douro, the wines were shipped to Oporto down the Douro river. The wines subsequently took their name from the city they were shipped from, Oporto translating to Port. To prevent the wine from spoiling during its long sea voyage to England, the wines began to be ‘fortified’ by adding a little brandy. While the motivation for fortification and the process today are very different, it’s likely that's how Port came to be a fortified wine.

An innovative region since its earliest days, the advent of uniformly sized bottles in the late 18th century allowed for the emergence of vintage Port – that is wine made from a single year’s harvest. This was because bottles could be easily stored in producers’ cellars rather than in barrels. Port lodges began bottling wines from a single – vintage Ports – in 1775, twelve years before the first vintage Bordeaux was created by Château Lafite in 1787.

Since then, vintage Port has become popular throughout the world, and while technology, styles, and even the grape varieties used to create Port wine have changed, it remains essentially the same as it was all two hundred and fifty years ago.

Where is Port made?

Port is made in the Douro Valley in northern Portugal to the east of the Marao Mountains. This stunningly beautiful region consists of steep slopes into which terraces – ‘patamares’ - are often cut in order to allow for the planting of vineyards. The climate is Mediterranean in the west with warm summers and plenty of rain. But as you move east, and into the main Port grape growing areas, so the influence of the Atlantic Ocean wanes and the climate becomes continental. Winters can be bitingly cold and summers blisteringly hot, sometimes reaching over 40°C /104°F Rainfall is low, averaging around 300mm per year. By comparison, Bordeaux receives around 900mm per annum.

The soils of the Douro River Valley consist predominantly of schist – a coarse-grained metamorphic rock – and granite with some limestone. The region is divided into three zones that sit west to east on the banks of the River Douro. These sub-regions are:

- Baixo Corgo –the westernmost region, it enjoys a cooler, Mediterranean climate. Grapes here are usually destined for tawny and ruby Port, though some vintage Port does get its fruit from here. A large amount of the grapes planted here are used to produce table wines, many of which are outstanding.

- Cima Corgo –also known as Upper Corgo, lies to the east of Baixo Corgo. Centred on the town of Pinhao, many of the leading Port lodges have their wineries here. Limestone dominates the soils, which adds a freshness and delicacy to the wines.

- Douro Superior –the most easterly region. Owing to the challenging geography, which is dissected by river rapids, heat and lack of rainfall, it has the lowest production of the three regions. As the name suggests, it’s also regarded as the finest and its grapes are often used in the production of vintage Port.

Which grapes are used in the production of Port?

Portugal is home to more grape varieties than any other country on Earth. While viticulturists are still sifting through Portugal’s vast grape library, at least 250 are known to exist. When it comes to the production of Port wine, there are an astonishing 112 recommended and permitted varieties to choose from. The leading shippers tend to cultivate just a handful though, including;

- Tinta Francesca

- Touriga Nacional

- Tinta Roriza

- Tinta Barroca

- Tinta Cão

- Touriga Franca

Below is a short biography of the main Port grapes and what they contribute to the final blended wine.

Touriga Francesa

The most widely planted variety, Touriga Francesa, or Touriga Franca as it’s known, is a consistent and reliable producer of top-quality grapes. It has much in common with its cousin Touriga Nacional in terms of fruit concentration and tannic structure, but it differs in many important ways. It’s subtler, noticeably less intense and powerful and has a floral element to it that gives an extra dimension to the great wines of shippers like Graham and Taylor’s.

Touriga Nacional

Arguably the finest variety and one that is finding favour in California, Australia and now in Bordeaux. This heat-loving vine is largely responsible for giving Port its weight and power. Its small, thick-skinned berries give low yields and produce dark, concentrated, tannic wines that are packed with fruit. Sometimes referred to as the muscles in vintage Port’s body, it’s a fine grape that makes excellent table wines too.

Tinta Roriz

Tinta Roriz (Spain’s Tempranillo) is becoming an increasingly important variety in the production of Port. Thanks to its ability to thrive in dry years and its early-ripening nature, it is ideal for the climate change-affected Douro. Drier, hotter years are leading to shorter growing seasons and Tinta Roriz is seen as a solution to this problem. Its grapes tend to give well-structured, aromatic, fruity wines that are capable of lasting for many, many years.

Tinta Barroca

Tinta Barroca gives fragrant wines that are sweet, soft and rounded. Like Merlot in Bordeaux or Grenache in the Rhône, it’s not a grape that’s noted for its high tannin content but is one that can help round out the austerity of other grapes. It also shares these grapes' exuberance for producing sugar and high yields so it tends to be found in cooler areas to keep it from running riot.

Tinta Cão

One of the most ancient varieties in the Douro, Tinta Cão is extremely well-suited to the region’s hot, arid climate. Giving small bunches of tiny grapes, Tinta Cão brings acidity to the mix and adds a measure of reserve to the wines while imparting elegance over time. Again, its most noticeable in the grandest shippers’ wines, especially as they age.

Is Port wine a blend?

Yes, virtually all Port wines are a blend. This is because different grapes give different flavours and characteristics, which when taken together, produce a wine that is greater than the sum of its parts. Port is also blended as producers need to find a consistent ‘house’ style. In any given year, only 2% of production is of vintage wine. The rest is dominated by things like ruby and late bottled vintage (LBV) Port, which producers want to taste the same year in, year out, in the same way that Champagne Houses want their non-vintage wines to be consistent. Blending wines allows them to maintain this consistency.

How is Port wine made?

There are three main ways of producing Port, and they differ in the way the grapes are pressed and the wines treated prior to going into barrel and bottle. These methods are:

- The traditional way – harvested grapes are loaded into granite or concrete vats known as lagares. Barefooted people then climb in and march up and down the lagares, pressing the grapes underfoot. The downside to this method is it is slow, exhausting, and requires plenty of labour – something the Douro is chronically short of – and controlling the temperature in the lagares can be difficult. The upside is that the quality of juice is superior.

- The modern way – this involves pieces of machinery called autovinifiers. Grapes are loaded into sealed steel or aluminium tanks. As the grapes begin to ferment and the pressure builds, the juice is driven from the bottom up a pipe to a reservoir at the top, and this sprays the ‘cap’ (grape skins that have floated to the surface), helping to extract colour. This method is efficient, but some have questioned the quality of the juice that’s collected.

- The ‘new’ modern way – this uses robotic lagares. These use robotic ‘feet’ to effectively mimic the marching motion of people as they press the grapes. These have the advantage of being efficient and of being able to run for long periods of time – something that can be vital in wet or excessively hot years when grapes need to be brought in and pressed in a hurry. They also produce high-quality juice.

Many producers use a mixture of these methods, though when it comes to vintage Port from the finest shippers, the traditional way is often favoured.

Whichever method is chosen, once the juice has been extracted, the ‘must’, as it is called, is inoculated (dosed) with yeast and fermented. Fermentation usually takes place in steel tanks as they give greater control over things like temperature. Fermentation typically only lasts for 36-48 hours until the wine reaches around 8% alcohol. Leave it too long and the yeast will consume the sugar and you’ll end up with a dry wine which is no use for the production of Port.

When it reaches the required level of alcohol, it’s ‘shocked’ by the addition of a neutral grape brandy at roughly one part spirit to four parts must. This addition of a spirit stops the fermentation by killing off the yeast. As the fermentation hasn’t been completed, the wine still has a high level of unfermented sugar in it, which explains why Port has that lovely luscious sweetness to it.

The finished wine is then ‘racked’, a process that separates the wine from the skins – into barrels. Many cheaper Ruby ports aren’t racked into barrels but are simply filtered and bottled. Depending on what type of wine they are destined to become, the length of time in the barrel will differ:

Vintage Port - wines age faster in the barrel than in the bottle, so vintage Ports are legally only allowed to spend up to 30 months in barrel before they are bottled. They are bottled with their sediment, which allows them to continue to develop in bottle for decades.

Late Bottled Vintage Port - receives anywhere from 4-6 years in cask, depending on the year and the producer’s requirements. Typically these aren’t bottled with their sediment.

Tawny Port – all tawny Port gets a minimum of 6 years in barrel, but they can be aged for 10, 20, 30, 40 years or more. Very old examples of these wines are regularly topped up to prevent excessive oxidation. Tawny Ports aren’t bottled with their sediment and so don’t need decanting.

Crusted Port – gets 4-6 years in barrel and is then bottled with its sediment.

What role does barrel ageing play in the production of Port?

The use of oak barrels in the production of Port is widespread, with the main aim being to help the wines develop through oxidation. Unlike many of the great wine regions, the use of new oak, which imparts a buttery flavour and wood tannins that help a wine age, is rare. The point here is to help the wines mature and add to their character through oxidation. The speed of this process is largely determined by the size of the barrel that’s being used. Port barrels – or ‘pipas’ range in size from 150 litres to the standard 550-litre barrels right up to vast ‘balseiros’ which can be 50,000 litres or more. In smaller barrels, the effects of oxidation are faster and more profound as the air-to-wine ratio is higher. Tawny, or wood Ports, tend to be aged in smaller casks, and the effects over time is to leach the colour and give the wines a nutty, fresh flavour.

Which Ports need decanting?

If the wine is bottled with its sediment – so single quinta vintage Port, vintage Port, and crusted Port – then they will need to be decanted. Ideally, these wines should be stood up for 24 hours before opening, as this allows the sediment to fall to the bottom of the bottle which makes decanting them easier. If you have a piece of muslin handy or even a tea strainer, this can be good for catching smaller particles. Remove the cork and pour the wine slowly and steadily into a decanter. If you try and decant Port too quickly, you’ll disturb the sediment – or ‘crust’ as it’s known – and that will end up in the decanter too.

Decanting not only removes the sediment from the wine but also introduces air, which will bring out the aromas and flavours of the wine.On very old bottles of Port, specialists sometimes use port tongs. These look a little like barbecue tongs and are used to take the neck of the bottle off when the cork is either too fragile or too stubborn to be removed. The Port tongs are heated up and then placed on the neck where they snip the top off. It’s a spectacular sight but one that needs practice. We’ve seen it done, and the bottle’s shattered, leaving owners to cry over spilt Port!

How long can Port age for?

The vast majority of Port wine is designed to be drunk on release. This includes late bottled vintage and tawny Ports, which, as they have had their sediments removed, won’t develop further in the bottle. Crusted Ports can develop further, but these are also intended for drinking on release or within a few years of being purchased.

Vintage Port, including single quinta vintage Ports, require ageing and can take many years to reach maturity. 1977 vintage Port, for example, is only now reaching its peak. 1977 was an exceptional year for vintage Port, giving powerful, hugely concentrated wines that will probably last for a century or more. Other vintages – such as the 1983s – are at their peak now. The best way to see the potential life of a vintage Port is to consult a vintage Port chart.

As a rough guide, a vintage port from a great year – 1963, 1970, 1977, 1985, 2001, etc. – will be capable of developing for 50+ years after release. Vintage ports from good vintage years – 1975, 1983, 1991 – will be good for 30+ years after release. Single quinta vintage Ports generally drink well younger, but the best can still easily develop over 20 years or more.

How does the flavour of Port change with age?

Only Ports that have been bottled with their sediment – so single quinta vintage, crusted, and vintage Ports – improve in bottle over time. Others like late-bottled vintage wines, just slowly fade away. Vintage Ports have three stages of development:

- Primary – deeply coloured, purple with crimson highlights. Fragrant with lots of sweet-smelling fruit, dark spices, chocolate and a big, juicy, sweetly toned palate with a hint of warmth at the end. Young vintage Ports can drink surprisingly well, depending on the year, but the sweet fruit and extract mask the full glory that comes with time.

- Secondary – depending on the wine and the vintage this period may come anywhere from five to twenty years after the vintage. The colour has faded to a rich deep red with amber highlights. The nose is complex, with fruits of the forest, woodsmoke, dried cherries, plums exotic spices and herbs. On the palate, the power has subsided a little, but there’s much greater complexity and subtlety. The Quinta do Noval 1985 was in this glorious stage in early 2019 and will remain there for another decade or so.

- Tertiary – for this stage we’ll reference Taylor’s 1955 which we drank in June 2022. Rich red-brown with an apricot-coloured rim. Fragrant, complex nose mixing dried white fruits, wax, honey, mixed nuts, and citrus. Noticeably lighter on the palate, the intensity of flavour is remarkable. A tour de force of dried white fruits, honey, raisins, mint, Camp coffee, and spices.

How do you store Port wine?

Single quinta and vintage Ports often need time in bottle if they are to show their best. Unlike Champagne or some lighter red wines, vintage Port is a sturdy wine that will tolerate sub-optimal cellaring. If you want to cellar Port until it’s ready to drink, then make sure it’s:

- Stored on its side – this will keep the cork moist and stop it from crumbling and the wine being lost.

- Keep it somewhere dark – UV light can damage wine, so find somewhere dark.

- Place it somewhere cool– heat will accelerate ageing and can damage the wine’s aromas. While most of us don’t have the luxury of a subterranean cellar, an under-the-stairs cupboard or a corner of the garage can work well.

- Avoid storing it where it will be subject to vibration– this can damage the cork and affect the maturation.

- Find somewhere where there’s enough humidity – a bone-dry environment can lead to the cork drying out. Traditional British cellars had reasonably high levels of humidity, and these have proved ideal for ageing Port. One side-effect has been that the labels will either come off or rot over time. This is perfectly normal and is why many producers emboss the capsules with the vintage so they can still be identified, and why so many old Ports come without labels.

How do I build a vintage Port collection?

If you’re looking to start a vintage Port collection, there are a few things to consider:

- Where will you store it? If you don’t happen to have a subterranean cellar and you want to store a quantity over the long term, it’s worth thinking this through. EuroCaves and other electric cellars are good, but capacity is limited. Companies exist that provide professional cellarage facilities for a fee; you may want to look into these.

- Buy wines young - the prices of vintage Ports tend to rise as they age, so if you’re looking for a cost-effective way of building a Port collection, buy them young and age them yourself.

- Buy a selection of vintages from different producers– that way, you can try different things out, and while you wait for the 2018s to come around, you can enjoy the 1985s.

- Buy by the case and the bottle– buy young wines by the case and dip into them as they mature. Buy older wines by the bottle when they are ready to drink.

Is vintage Port a good investment?

Historically speaking, not really. In recent years, however, demand for the top wines has increased, and they are now regarded as investment-quality wines, especially in great years.

How long does Port last after opening?

There is an assumption that once opened, Port will remain good indefinitely. While it’s true that these wines can last well after opening, they will deteriorate with time. A bottle of ruby Port is usually good for a couple of weeks with the stopper in. A bottle of LBV can last a few weeks as it has a greater level of concentration and as it has spent years in barrel. Tawny Port can also last a long time. The level of oxidation these wines see means they fade slowly.

With a vintage Port, it all depends on the year and its age. A young vintage Port from a great year – say from 2011 - with a decade of bottle age should be good for several days. On the other hand, a mature wine, even from a great vintage such as 1955 will need drinking up within a day or so. The 1955 Taylor we had was glorious, but just a day or so later it had begun to crack up as the fruit faded and the acidity rose.

What is vintage Port?

Vintage Port is a fortified red wine made from a single year’s harvest. It is only made in exceptional years – typically around three times a decade – and is ‘declared’ by the Port producers. It’s a rare wine that can age and develop for decades if stored properly. It’s bottled with its sediment, so it needs to be decanted before drinking.

What types of Port wine are there and how do they differ?

There is a myriad of ways you can categorise Port. By where it spends the majority of its life – either in the barrel or bottle, so-called ‘wood Ports’ and ‘bottle aged Ports’, or you can look at its colour – red, rosé, or white.

In an attempt to give a simple answer the question of what types of Port are there and how they differ, in this guide we shall take a comprehensive view and discuss the following types – ruby, tawny, white, rosé, crusted, late bottled vintage (LBV), reserve, single quinta vintage and vintage Port.

Ruby Port – these are Ports which keep their deep red colour as they are aged in large containers – sometimes large wooden barrels, else stainless-steel vats - which means there is less oxidisation. Aged for no longer than three years, these are Ports that are meant to be drunk young.

One form of ruby Port is Vintage Character Port which are premium ruby Ports with a mature style. They are made from a blend of good-quality wines from several relatively recent vintages. They are aged in bulk (usually in large oak barrels) for up to five years, which enables them to retain their ruby-red colour and rich fruit.

Reserve Port – these are ruby Ports which are made from better grapes and aged in barrels a little longer.

Tawny Port – in contrast to ruby Ports, a tawny Port is aged in smaller wooden barrels, where they oxidise heavily, losing the redness and producing a Port that appears light brown in colour. Reserve tawny Ports are kept in barrels for a minimum of 6 years. Tawny Ports can be given an age statement, denoting the average time in wood – 10 years, 20 years etc. You can also get colheita Ports, which are tawny Ports made from grapes from one exceptional year, the bottle label will tell you which year that is. These are also known as vintage tawny Ports.

White Port – perhaps unsurprisingly white Port is made from white grape varieties such as Viosinho, Malvasia Fina, Códega and Rabigato. A lighter style of Port, the majority of white Port is bottled young, though as with tawny Port you can find some with an age statement. White Port is usually quite sweet, with flavours of peaches, melon and nuts, and is the type of the Port that’s best suited to serving as a long drink when mixed with tonic, soda, or lemonade.

Rosé Port – the newest style of Port, being introduced by Croft in 2008. Typically made from a blend of grape varieties, when making rosé Port the juice is given minimal contact with the grape skins. This creates a pink colour and produces a less tannic wine.

Crusted Port – another relatively new style of Port, crusted Ports are made from a blend of multiple harvests, are matured in barrel for 2-4 years and then bottled unfiltered. They must be kept in the bottle for a minimum of 3 years. The crust is the sediment that forms in the bottle and so this type of Port will require decanting similar to a vintage Port.

Late Bottled Vintage Port – also known as LBV Port, was introduced in the 1950s and is said to be the result of producers having lots of unsold vintage Port (how times have changed…) LBV Ports, like vintage Port are made from grapes from a single year but spend up to 4-6 years in barrel, twice the length a vintage Port would be allowed. Leaving the wine in the barrel for longer means that these wines can be enjoyed younger than a vintage Port.

Vintage Port – vintage Port is the jewel in the Douro’s wine crown. It is only made in the finest of years and is produced using grapes from a single year’s harvest. On the label, they bear the year from which the grapes were grown, e.g. 1977, 1980, 1983, etc. Vintage Port isn’t made every year; rather, it’s ‘declared’ around 3 times every decade when the producers deem the quality to be sufficiently high. These wines only account for around 2% of the region’s production. Vintage Ports are kept in barrel for just 2 years, bottled unfiltered so providing the wines with the most ageing potential. The best wines can age for decades.

Single-Quinta Vintage Port – in years which aren’t declared as vintages, the finest fruit goes into single quinta vintage Ports. These are made in the same way as vintage wines, and can offer exceptional value for money.

What does a ‘vintage declaration’ mean in Port?

Unlike most regions where vintage wines – wines that are the product of a single year’s harvest - are the norm, in the Douro Port producers ‘declare’ a vintage only when the year is of exceptional quality. Vintages aren’t declared every year and even in declared years, not all producers will declare one. A famous outlier in this regard is the rare single vineyard wine, Quinta do Noval Nacional. Quinta do Noval Nacional, or Nacional as it’s also known, declared a vintage in 1962 which few others did, but didn’t declare in 1977 when pretty much everyone else did.

If you take a historical view, vintages are declared roughly three times every decade. These can be spaced out as 1970, 1975, and 1977, or come in a rush as with 1991, 1992, 1994, and 1995. As in Champagne, where vintages are the exception rather than the rule, commercial considerations play a significant part in a shipper’s decision as to whether to declare or not. The invention of late bottled vintage Port was a direct response to shippers having too much wine, and it was only with the revival in interest in Port in the 1960s and 1970s that full vintage Ports became commercially attractive again. Then there are special years that shippers feel they must declare. Take Taylor’s in 1992. 1992 marked its 300th anniversary, so it came as a surprise to no one that Taylor’s 1992 vintage Port was made. The fact that it’s one of the greatest wines this phenomenal shipper has ever made is a happy coincidence.

Are there any regulations or standards governing the production and labelling of vintage Port?

Yes, like most wine-producing regions, the regulations surrounding the production of Port are extensive. Everything from the grapes that can be used to the way wines are aged and what can appear on the label is regulated by The Port and Douro Wines Institute, an official body belonging to the Portuguese Ministry of Agriculture.

They are also responsible for rating quintas (vineyards) and grading them from A to F, A being the finest, and F being the poorest. These ratings are based on factors such as:

- Vine planting densities

- The quality of the microclimate

- Soil type

- Average vine age

- Aspect

- Altitude

- Gradient

- The amount of granite and schist in the soil

- The type of grapes planted

Each element is given a score and a total is awarded. To achieve an A-rating, it needs to score 1,200 points or more, while F-rated vineyards are ones that score 399 or less. These ratings matter as the higher a quinta’s rating, the more grapes the vineyard is permitted to harvest and they can expect a higher price for their grapes/and or wine. A similar rating system occurs in Champagne – the Échelle des Crus. Vineyards are rated from 1% to 100% (in practice, it’s 80%-100%) with a Premier Cru vineyard scoring 90-99% and Grand Cru vineyards scoring 100%.

What distinguishes a great vintage from an average one in the world of Port wine?

Vintages – a year’s growing season – matter in the Douro as much as they do in Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne or Rioja. Excessive heat can lead to wines that have a ‘scorched’ taste to them. Equally frost or rain-affected years can lead to tiny crops of irregular quality fruit that makes for lesser wines. Happily, with Port you don’t need to be a fount of vintage knowledge to choose a great wine. If it’s a vintage Port then it would have been made in a great year. The difference between a great vintage and a good vintage comes down to things like the levels of concentration in the wine, how long they will age for, and their complexity.

What are the best vintages for vintage Port?

We looked at this in depth in our Vintage Port Guide, where we looked at every declared vintage since 1900. Our top ten post-war vintages would be:

1945

1955

1963

1970

1977

1985

1991

1992

2007

2011

This is a matter of personal taste, of course. Whether you favour power over refinement, youthful fruit over aged complexity, will have a bearing on which years are better for you. For example, the 1970s are generous, powerful wines that are an absolute joy. The 1977s on the other hand are more structured, tannic Ports that even now are firm, powerhouses.

Which is the best Port producer?

The question as to which is the best Port producer is one we have discussed many, many times over a glass of Port. The MWH blog contains several producer profiles, after the writing of which we did decide which is the best Port shipper. Again, this is a matter of taste, but our top five would be:

5. Dow – traditional, powerful, well-structured wines that can age for decades even in moderate years. Impeccably made, these are wines for lovers of old-style Port.

4. Fonseca - they are not wines for the faint of heart; they are bold, dramatic wines that have a style that is uncompromising, all their own, yet brilliant.

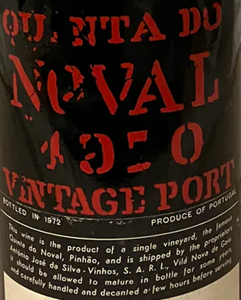

3. Quinta do Noval - stylistically their best wines tend to be full-bodied, well-structured and built for the long haul.

2. Taylor – known for their immense power and sublime concentration, Taylor’s wines are also elegant and precise. Wines like the 1966, 1970 and 1992 are Port legends.

1. Graham - combining power with elegance, Graham’s wines display a level of subtlety that is utterly beguiling. The 1945 Graham is one of the greatest Ports of the twentieth century.

In truth, all these producers are exceptional, and their wines never fail to please. When it came to the top spot it was like asking if we’d like to drink Mouton Rothschild or Lafite Rothschild. Our answer would always be, ‘Both’.

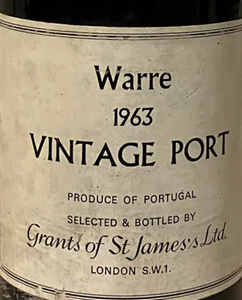

Why do some Port wines have wine merchants names on them?

You’ll often see names such as Grants of St. James, Augustus Barnet or Berry Brothers and Rudd on the label of old bottles of Port. These appear as merchants used to go direct to shippers such as Warre or Croft and arrange their own bottlings.

How does the terroir influence the flavour profile of vintage Port?

The French concept of ‘terroir’ is particularly interesting when it comes to Port. Terroir is the sum effect of things like soil, rainfall, drainage, and altitude that have an impact on a vineyard and the fruit its vines produce. With its steep, winding, undulating vineyards, the Douro is full of microclimates and microsites, all of which have a bearing on the terroir of those vineyards. As Port is a blended wine, it would be easy to imagine that these influences are lost in the blending and in the case of lesser wines, that’s probably true. But when you get to the single quinta and vintage Ports, such nuances are prized and can play an important role in creating the finished wine. For example, in hot years, a vineyard in Cima Corgo, which has a particularly high concentration of limestone in the soil and a high elevation, can give the freshness needed to balance out the lower acidity wines from elsewhere.

As in many wine-producing regions, a lot of research has been carried out into terroir in the Douro in recent years as producers strive for ever-greater wines. And while single vineyard wines where the terroir is most marked are rare – the obvious example being Quinta do Noval Nacional – the overall effects of terroir on vintage Port are hard to overstate.

Are there specific vineyard sites in the Douro Valley known for producing exceptional grapes for vintage port?

Most Port shippers have cherished sites that consistently produce outstanding fruit, but Quinta do Noval Nacional is the most famous. Nacional is a one-off. A tiny parcel of ancient vines – they are thought to range from between 35-80 years old – that are on their native rootstocks rather than on American rootstocks. This may not sound significant, but it is.

In 1868 the phylloxera beetle arrived in the Douro Valley and destroyed many of the finest vineyards by attacking the roots to drink the sap. To combat this blight, vineyards were ripped up, vines burnt, and new ones planted that were grafted onto more resistant American rootstocks. Effective as this was as American vines are resistant to phylloxera (to an extent) something was lost in terms of quality.

Thanks to constant fumigation, the vineyard’s elevation and soil composition, the Nacional vineyard was saved. The tiny amounts of grapes it produces creates wines that have a richness and weight that is off the charts. Only produced in truly exceptional years, years that don’t always coincide with standard vintage declarations, the fruit is pressed by foot in concrete lagares and aged in 2,500 litre barrels before bottling. In essence, this is a 19th-century approach that produces a 19th-century tasting wine.

While many vintages of Nacional have been made over the years, bottles remain scarce. This is because they only produce between 10,000-20,000 bottles, and those that are released are seized upon by collectors. The Quinta do Noval Nacional 1963, for example, has been described as the ‘most sought after Port in the world’ and with Robert Parker giving it a drinking window of 1996 -2096, it’s a wine that will only become more sought-after as it continues to develop.

As we said, Nacional isn’t made in every year. Below is a list of current releases. All are wonderful in their own way, though prices can be high:

2011, 2004, 2003, 2001, 2000, 1998, 1997, 1996, 1994, 1991, 1987, 1985, 1984, 1983, 1982, 1980, 1978, 1975, 1970, 1967, 1966, 1964, 1963, 1962, 1960, 1958, 1955, 1950, 1945, 1934, 1931

How is climate change affecting Port wine production?

The climate in the Douro is surprisingly delicate, and variations of a few degrees, a change in total sunshine hours, or a rise or fall in the amount of rain received can make or break a vintage. Sadly, all of these factors are being affected by climate change. Helda Fraga in her book, ‘Viticulture and Winemaking under Climate Change’ described the Douro as a ‘climate change hotspot’. Summer temperatures in the Douro only occasionally exceed 40°C, but that’s set to change as temperatures rise year on year. The region is also seeing a greater number of deluges of rain, hail, and spring frosts.

Winemakers are doing what they can to reduce the effects. Better canopy management, reliance on old vines (which can dig deeper for water) and looking to higher-altitude vineyards are all techniques that are being used. Wineries are also looking to conserve water, use less electricity, and generally act in a more sustainable way.

There seems little doubt, however, that in the short-term at least, things will get harder, vintage Port’s character will change, and further steps will need to be taken to protect this unique region’s wines.

Which are the best-value vintage Ports?

Vintage Port remains a very well-priced fine wine. The finest examples – leaving aside the ancient and the super rare such as Noval’s Nacional – can be yours for far less than the equivalent quality Bordeaux or Burgundy. But if you’re looking for beauty on a budget, we’d recommend looking for:

- Lesser-known shippers in great years – while Taylor, Graham, and Dow are the names most people know, their wines are usually among the most expensive. Other less well-known shippers such as Churchill, Sandeman, Croft, Delaforce, Martinez or Duff Gordon can still provide exceptional pleasure for less money. For example, Taylor’s 1970 will cost you £192 a bottle, whereas Smith Woodhouse’s 1970 is £102.

- Single quinta vintage Ports – single quinta ports used to be seen as something of a poor relation to vintage Ports. Some people were sniffy about them, regarding them as ‘second wines’ made in less than great years. While it’s true they aren’t made in declared vintages they are often brilliant. Ports like Taylor's Quinta de Vargellas, Warre's Quinta da Cavadinha and Dow’s Quinta do Bonfim are all exceptional.

How does Port compare to other fortified wines such as Sherry and Madeira?

All fortified wines are essentially made by adding a distilled spirit of around 77% to wines. These are usually a flavourless grape brandy which ‘fortifies’ the alcohol content and, in the case of Port and Madeira wine, it stops the fermentation process by killing the yeast so that any residual sugar remains within the wine.

The notable exception to the above is Sherry. In Sherry, the fermentation isn’t stopped but allowed to complete naturally so giving a dry wine. This is then fortified to bring up the alcohol level to between 18% and 20%. Sweet Sherries get their sweetness from the addition of sweet wines or, in cheaper wines, syrup rather than from unfermented sugars in the wine.

In terms of taste, Port, Sherry, and Madeira are very different:

Port – is, as we’ve said, a red fortified wine that while coming in a range of styles, is essentially slightly sweet.

Sherry – is a white wine, that’s either dry – Fino, Manzanilla and dry Oloroso, for example – medium-dry – cream Sherry such as Croft Original – or fully sweet – wines labelled as ‘dulce’.

Madeira – is a white wine – though the colour is invariably brown owing to the effects of oxidation. It can be dry – Sercial, medium-dry – Verdehlo, medium-sweet – Boal or Bual or sweet – Malmsey. Confusingly, these are not the only terms you will see on labels as there are a host of other grape varieties that can be made into dry or sweet styles, such as Bastardo. All Madeira wines have a distinctive ‘caramelised’ character which comes from then being heated, either by the sun or in vats. They also have a marked acidity that makes even the sweetest styles fresh and clean.

How do you drink Port wine?

While there are some strange rituals surrounding drinking Port – Port is always passed to the left, clockwise round the table, and it used to be prescribed as a treatment for ulcers. In the main, you can drink Port as you would any other fine wine, though to get the best from it try to:

- Use the right glasses – standard wine glasses are fine. The small Port glasses, sometimes known as ‘schooners’ that were popular in the twentieth century, when filled to the brim are lousy for serving Port. Fill a normal wine glass around a third full and you’ll be able to enjoy the aromas and flavours of this enchanting wine.

- Serve it at the right temperature – tawny Ports are best served with a slight chill to them, whereas late botted vintage and vintage Ports are best served at room temperature.

- Decant Vintage Ports– this also goes for crusted Ports and single quinta vintage ports. Decanting is simply the process of separating the wine from its sediment.

- Drink Port with food– it goes extremely well with cheese, red meats, and even puddings.

- Enjoy it responsibly – Port has a significantly higher level of alcohol and, in the case of vintage wines, isn’t the purest of wines and will give you a filthy hangover if you overdo it!

How does the alcohol content of vintage port compare to other wines?

The average bottle of wine has an alcohol content of around 12%, though it can be as low as 5.5% for some very sweet wines, and as high as 16% or more for wines made with high-sugar grapes such a Grenache or Zinfandel. Reportedly the alcohol content in wines globally has been on the rise due to the increased sugars in harvested grapes. Whether this is being brought about as a result of climate change or just for stylistic reasons is debatable. When it comes to fortified wines, such as vintage Port, the alcohol content can start at around 16.5% but typically it’s around 20%.

What are the common misconceptions about vintage Port?

Here are our 3 top misconceptions about vintage Port:

- When a Port bottle has a year on the label it’s a vintage Port - as we’ve discussed in our earlier section on the different types of Port – colheita, LBV and single quinta Ports are all made from grapes from one year’s harvest. But only vintage Port made in declared “vintage” years using prescribed methods can be called a vintage Port.

- Port should only be drunk as an after-dinner drink with cheese, particularly blue cheese - while vintage Port can of course, be paired with your after-dinner cheese board, we’d argue that the true pleasure comes from drinking this wine on its own in the company of good friends or with suitably fine foods (see below).

- Port is for Christmas – while Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without a glass or two of Port, it’s a wine for all seasons. White Port can be mixed with tonic to create a refreshing long drink, and tawny Ports are brilliant served chilled on a summer’s evening.

Can you recommend some foods to go with Port?

Port is a surprisingly food-friendly wine. Tawny Ports are the perfect accompaniment to cheeses or creamy caramel puddings, as the acidity can cut through the richness. Rich meat dishes such as duck, venison, ostrich or steak and kidney pudding are even better with a glass or two of late bottled vintage Port, the ample fruit and hint of sweetness bringing out the best in the food and the wine. Fresh berry puddings are delightful with a rosé Port, and if you’re a fan of nuts, we can wholeheartedly recommend a 10-year-old tawny such as Dixon’s Double Diamond.

Like Some Vintage Port Help?

We hope you found this Port wine guide of interest. If you are looking for a specific Port, then please do get in touch by calling Mike on 0118 984 4654 or by emailing MWH Wines. A recognised authority on all kinds of Port, he’ll be happy to advise you on which wine is right for you.